I started this blog towards the end of 2020 after I handed in my dissertation on priests, books and compilatory practices in the Carolingian period.1 It was initially intended as an online space to store (unfinished) ideas for future research projects. Over time, however, I started to use the blog more as a channel to communicate my academic publications and participation in various projects. Additionally, it has played a substantial role in my teaching as a way to present large swaths of information in a somewhat orderly fashion.

For now, I aim to keep on using the blog this way. So on here, you will primarily find my latest publications, books reviews, blogs I have written elsewhere, digital humanities projects, and the occasional personal update.

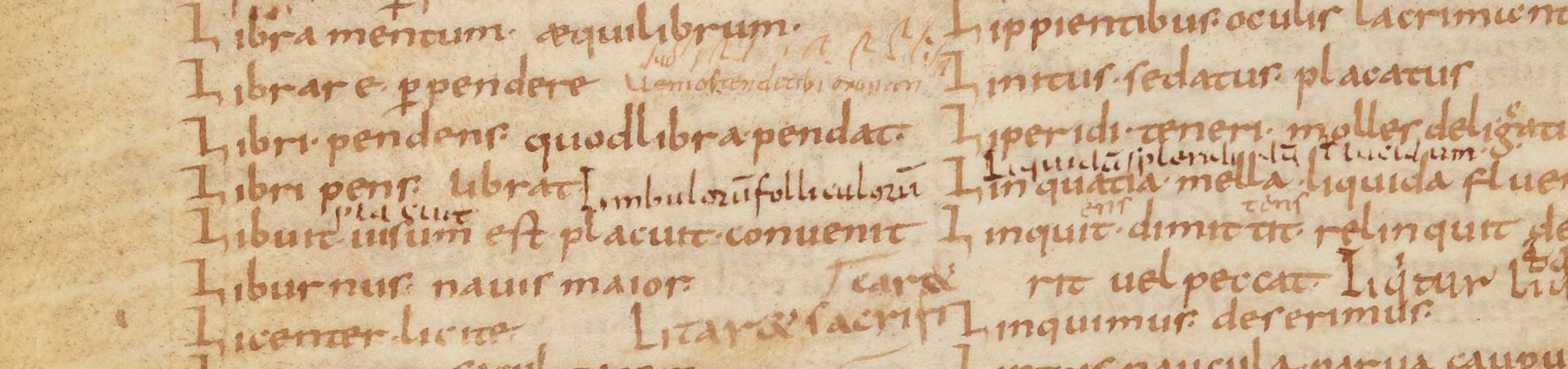

Libripendis

Coming up with a name for this blog was more difficult than I thought. That is why I resorted to a well-known means of coming across as interesting, which is latinizing one’s last name. As my last name is ‘Waagmeester’, a Dutch word describing the master of the weighing house, I had to look for a historical official that was in charge of managing weights. The earliest example that I was able to find is mentioned in Plinius’ (23/24-79 A.D.) Naturalis historia as the ’libripendes’ who were weighing the coins for the wages of the soldiers.2 How this function was understood later on, can be gained from a 9th-c. glossary (see above), where it is explained as ‘he [who] weighs’.3 Much later, in a philosophical lexicon from the 17th c., it is described again as ‘he who weighs and is in charge of the weighing affairs’.4 As such, the name ’libripens’ seems to be fitting for this blog. To avoid any confusion with an Austrian IT-company I have chosen the genitive singular, which gives it something personal as well.

Gaius Plinius Secundus maior, Naturalis historia, lib. XXXIII, c. xiii. ↩︎

Paris, BNF, Lat. 7641, f. 40v. On the glossary (abavus maior) and the glosses for which it is known, see Rolf Bergmann and Stefanie Stricker (eds.), Die althochdeutsche und altsächsische Glossographie: Ein Handbuch (2009), pp. 929-937. The manuscript used here is not mentioned in the study. ↩︎

Johann Micraelious, Lexicon philosophicum terminorum philosophis usitatorum … (1653), col. 592. ↩︎